Welcome to This World: Rabbett Before Horses Stricklands Paintings and Drawings

Reviewer Hannah Dentinger took in the new Rabbett Before Horses Strickland exhibition at the Tweed Museum of Art in Duluth, and she came away floored by both the vision and the virtuosic execution evident in the work she found there.

This show is spectacular in every sense. The large canvases in it are all fairly new, created over the past ten years by an artist who began painting as a young man but who is now enjoying his first museum show, hosted by the Tweed Museum of Art.

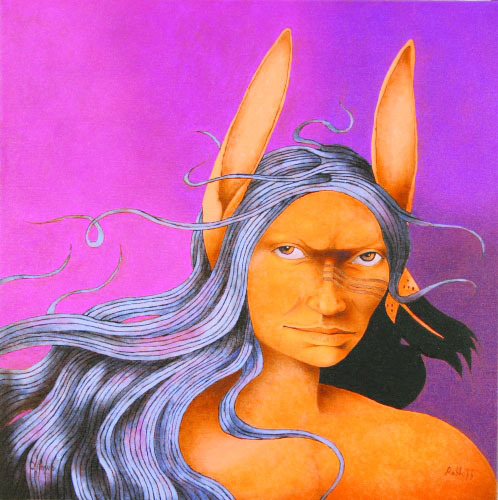

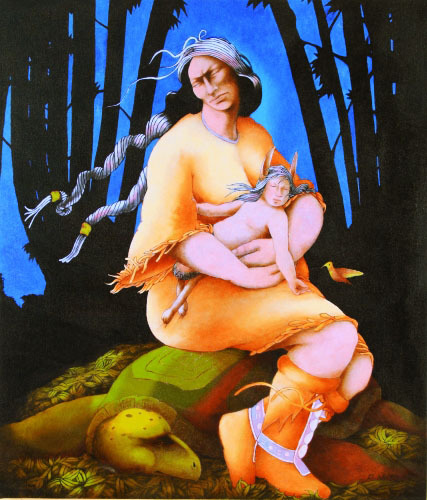

Rabbett Before Horses Strickland is a figurative painter in the Western European tradition that harks back to Renaissance artists like Michelangelo and Botticelli, whose influence he is quick to acknowledge. Indeed, Strickland’s muscular, sculptural figures, captured in a variety of dynamic poses, their limbs faintly outlined in black and modeled in lifelike color, recall the figures that people Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel. Again, in Creation of the First Butterflies (Gaa-oshi’aad Nitam Memegwanay) Strickland deliberately evokes Botticelli’s Primavera, quoting the fluid, slow-motion dance of the three Graces. Some paintings bring to mind early Renaissance frescoes in that Strickland often favors a frieze-like arrangement of figures against a background that is featureless and flattened, as in the exquisite Nanabozho Gaagiigido Wiijayaaw Ajiaak Wag (Nanabozho Talking to Cranes), or one that is bounded by far-off outcroppings of jagged peaks like those of Leonardo’s invention (see, for example, Eclipse or Story Telling).

What is most striking about these paintings, though, is their coherence. Not only does each painting convey a sense of unity through color and composition, but the entire collection is also unified in subject matter, tone, and style: the work is unmistakably that of Strickland and no-one else.

These pieces are coherent in another sense: many of Strickland’s paintings illustrate tales of the traditional Ojibwe character, Nanabozho, much as the Renaissance painters he admires drew inspiration from Greek, Roman, and Christian mythological source material. Remarkably, although the explanatory wall plaques that accompany some of the paintings are helpful in illuminating their content, the paintings themselves are more eloquent still—suggesting the truth of the cliché that a picture is worth a thousand words. These narrative canvases compare favorably with the work of Nicolas Poussin, whose paintings also frequently relate a story in a single image. In Strickland’s work, time seems to have collapsed upon itself so that the entire story happens at once. This is suggested by the multiplication of figures: half a dozen identical men and women carry out as many different actions in paintings like or Eclipse or Moving the Sun, as if all the panels of a comic strip had been superimposed.

Strickland’s style has a consistency and confidence that comes through particularly in his use of color. The blazing pink, almost neon clouds in Moving the Sun and a Maxfield Parrish-like aquamarine he employs to stunning effect in the nighttime scene Searching for Nokomis are bold choices, used unsparingly. In Searching for Nokomis, birch leaves glow bright blue among swollen, mottled ferns. Bill Shipley, Chief Docent at the Tweed and himself a painter, overheard Strickland explaining to viewers that the painting looks incredible under black light: a holdover, Shiply surmised, from the psychedelica of Strickland’s San Francisco youth. Strickland applies oils in thin and delicate layers (a technique called “glazing”) such that the weave of the canvas is clearly visible; and this, too, bespeaks an artist confident in his vision.

The composition of Searching for Nokomis (purchased, incidentally, by the Tweed) is extremely sophisticated: six figures on turtles proceed through a birch grove to a lake. The circle of figures interwoven with the vertical element of the trees keeps the scene from becoming chaotic, despite the abundance of detail. This is an arrangement that also serves Strickland well in the fantastical Ag Ki Gisiss (Out of the Sun). From a coastal forest, men and women watch as half-human, half-bird invaders come ashore, two of them perched atop monstrous creatures, shaped like round horses’ torsos missing any sign of a head. Their ship is visible in the distance. The woods are alive with animals: raccoons, deer, birds, turtles, even fish swimming in mid-air. A crow cocks its head, its beak parted intelligently, as though about to make a dire prediction. Strickland’s attention to detail—much like another visionary painter, Stanley Spencer, he paints every leaf, every strand of hair—is at its most virtuosic in this complex painting.

As Ag Ki Gisiss (Out of the Sun), with its nightmarish intruders hints, Strickland is not an apolitical artist. In Assimilation, a picture that is set on open water, one of the sinister avian invaders attempts to drag a Native into the tossing waves while Nanabozho and Nokomis try to help him back onto their turtle steed. The painting is an allegory of the violence of cultural repression: assimilation, it clearly suggests, is akin to drowning.

Strickland also takes a stand on a contemporary issue that ought to speak to many Minnesotans: the genetic modification of wild rice. He contributed the image used on the “Keep it Wild” campaign’s poster, and a similar painting can be viewed at the Tweed. In fact, Ricing is among the first pictures to greet visitors to the show. Thick, flexible grasses form a dense wall; individual grains of wild rice are carefully delineated. Nanabozho stands in a wide canoe striped with pitch on deep indigo water that, despite waves like hands slapping at the boat, seems immobile. Butterflies flock toward him, their opaque wings looking almost as dense as leather. Like bumblebees, they seem impossibly earthly, and their flight, all the more miraculous.

About the reviewer: Hannah Dentinger writes on art and literature. She is also a scholar of medieval Welsh literature.

What: Rabbett Before Horses Strickland: From Dreams May We Learn<br> Where: The Tweed Museum of Art, Duluth, MN

When: Exhibition runs through February 24, 2008

Admission is FREE and open to the public